Guidance for writing manuscripts

When should I start writing?

Now. Right away.

I get it: writing is difficult, a little intimidating, always exhausting. You might not know what you want to write about yet. You don’t have results. The story isn’t clear. You haven’t even cleaned the data.

But here’s the secret: writing isn’t what you do once you’ve figured out the story. Writing is how you figure out the story.

Think about the last time you wrote a proof. How did you do it? Certainly not by staring at the sky until BANG, a fully-formed argument flashed before your eyes and you wrote it down, perfectly, beginning to end. Nor was your last bit of Python code written out as one perfect, bug-free script. No, proofs and code emerge from an organic process: you sketch out a few tentative ideas, test them, scrap some, get inspired by some others, write some more, and on and on until you get that funny feeling in your chest that tells you you’re done. Prose is no different.

Writing, conceived like this, is a central part of the scientific process. It’s not just how we communicate ideas to others; it’s also how we communicate ideas to ourselves. Writing is the clearest way to expose holes in our research that need to be filled with new experiments. It’s the clearest way to achieve flashes of inspiration, made possible by seing our own ideas laid out linearly on a page. Waiting to write means passing up opportunities to be a more rigorous, thoughtful, and creative scientist.

But… how?

To achieve this, most of us need to re-frame our concept of writing. Microsoft Word and most other text-editing software (especially LaTeX!) re-enforce a bad concept of writing: as soon as you type your words, they show up on the screen in something that already looks like well-formatted sheet of paper. You feel the horror of having written something that looks so permanent. Someone will hold you accountable for what you’ve said. Better make the next words good ones.

And so the next words never come. The page stays mostly blank, and your fear of writing dials up one more notch.

A formidable barrier, to be sure. To fight against it, we need a powerful, constant reminder of what we actually believe about writing: that it’s a process, that it’s scrappy, that we’re not afraid.

There are various strategies to achieve this. One way is to never, ever start drafting something from the beginning and instead to dive right into the middle. Another is to hammer out your first few drafts with pen and paper. My favorite, though is:

The idea behind this is explained in a brilliant essay by the novelist Anne Lamott. It’s great reading, and you can find it here. The idea is that, in your first few drafts, literally anything goes. Lamott tells us:

You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page. If one of the characters wants to say, “Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?,” you let her. No one is going to see it. If the kid wants to get into really sentimental, weepy, emotional territory, you let him. Just get it all down on paper because there may be something great in those six crazy pages that you would never have gotten to by more rational, grown-up means. There may be something in the very last line of the very last paragraph on page six that you just love, that is so beautiful or wild that you now know what you’re supposed to be writing about, more or less, or in what direction you might go – but there was no way to get to this without first getting through the first five and a half pages.

This is geared towards creative writing, but scientific writing is no different. Send your cells up into space and let them experience zero gravity for an afternoon. Discuss how your neural net feels about ketchup on eggs.

Lest I forget that shitty is my aim, and the stuffy old habits creep back in, I often literally write the words Shitty First Draft on the top of the page, in big font, so that I can’t possibly fool myself into thinking that this is anything more.

Everyone’s set-point for how fanciful they’ll allow their shitty first draft to be will be different. I’m fairly reserved, so my “shitty first draft” usually just involves half-sentences, misspellings, and song lyrics that happen to pop into my head. The key is that it’s not just ok for this draft to be shitty: the goal is for it to be shitty, whatever that means to you. It’s the only way to counteract the stiff habits we’ve built up over so many years. It sounds crazy, but for me, it’s indispensible.

Types of manuscripts

Now, into the nuts and bolts. Each field has different standards around what constitutes a “publishable unit”. In many fields of computer science, communication happens mainly through conference proceedings. In mathematics, manuscripts range from a few hundred words to many pages, with no real limit on the number of figures (if indeed there are any figures at all), and few standards around how the writing must be structured.

Most of our work will be aimed at journals of medicine, public health, and biology. Within this scientific ecosystem, communication mainly happens through peer-reviewed journal articles. These articles usually fall into one of a few categories:

-

Research article: This is the main venue for communicating new scientific findings. These normally allow for about 3,000 words and 3 figures or tables (sometimes up to 5 if you’re lucky, or an unlimited number for online journals like PLOS and eLife).

-

Research correspondence: These are shorter manuscripts, usually 1,000 to 1,500 words, with up to one figure or table and a short list of references.

-

Perspective: These highlight key issues in the field but don’t usually present new research, and may take a more subjective stance. Most journals don’t allow you to submit these without an editor reaching out to you first.

-

Review: These are often around the length of a research article, but instead of presenting new research, they provide a succinct summary of key findings in a given field. Again, these are usually solicited directly by the journal editors, but some journals allow you to submit proposals for review topics without any prior communication.

The science itself usually dictates which of these is the most fitting venue. Journal webpages should have a tab titled “Information for Authors” where you can find the article types and requirements for that journal.

Structure

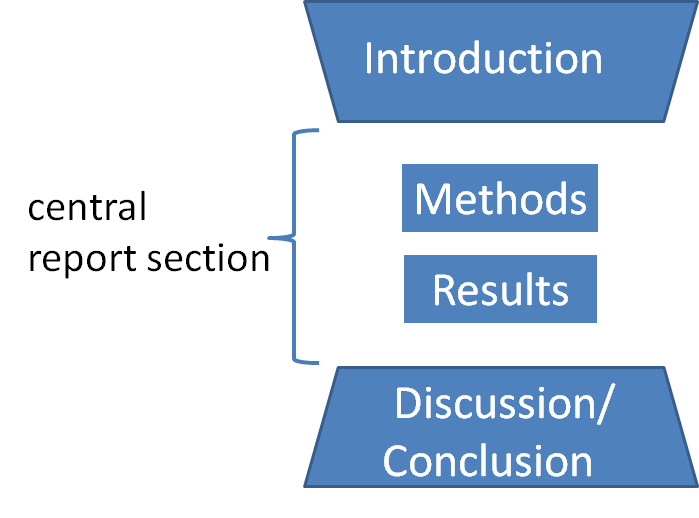

For perspectives and reviews, you can structure things however you like. For research articles and research correspondence, however, readers are looking for a very specific structure: the IMRAD structure. IMRAD stands for Introduction, Methods, Results, (and) Discussion. The Introduction is meant to start from broad principles and then to gradually drill down into your paper’s specific topic. The Methods and Results tell the reader what you did and what you found, with minimal interpretation. The Discussion provides the interpretation of what you found, and then zooms back out to place the research in a broader context. Most descriptions of the IMRAD format will include a schematic that looks something like this (from the Wikipedia):

where the width of each block corresponds to the breadth of your thinking at that stage in the manuscript.

But… this cramps my style

I get it. I was like you once, too. But I’ve become a staunch believer that this structure is not just in the reader’s best interest, but also the writer’s. Narrowing oneself to such a rigid structure allows you to be more creative in the things you fill each section with. Treated properly (see below), the structure provides a framework for thinking deeply and clearly about your research problem. It follows the narrative structure that we all know and love (setting, plot, climax, resolution), which means that its more interpretable to both the writer and the reader than any other structure. Learn it well, and I promise you will begin to feel freer and more creative, not less!

Read on for some thoughts on how to approach each section:

Introduction

The introduction is not a “background” section, where you walk the reader step-by-step through the miscellania that they’ll need to understand your methods. Instead, it’s an argument where you lay out the evidence for why your research problem is important, why it hasn’t been addressed yet, and why you’re the one to do it.

Introductions should begin with a sentence that succinctly describes why your research area is important. Statistics on morbidity or mortality can be effective, though they’re somewhat over-used. Other options include highlighting key, well-known areas of missing data or technology barriers that your research could address.

Once you’ve established the importance of your problem, then you can strategically begin to lay out the structure of existing knowledge in the field. Remember, this is an argument, so stay away from lists of facts, and instead use this section to give shape to the all-important gap: the thing that your research is going to address.

Every research paper should address a clear gap. It is the job of the introduction to clearly state what the gap is, why it exists, why it’s important, and why you (the researcher) can now do something about it. Everything in the introduction leads up to the gap, and everything in the rest of the paper follows from it.

So, you’ve argued that your research problem is important, and you’ve outlined the existing research and the things that have caused it to fall short. How do you cue to the reader that you’re about to tell them what the gap is? Through the use of the all-important, all-powerful word:

Use this word sparingly! Sometimes you will need to use it for something other than the gap, but only do so if you’ve slept on it and asked five of your closest friends for other ways to say what you’re trying to say. An introduction full of “howevers” makes the reader feel intellectually whiplashed, and by the time they reach the gap, you’ve watered down the word so much that they can’t tell what the paper is actually about. Use it once, and it will strike the reader to their core - seriously!

Finish off the introduction with a 1-2 sentence summary of what you’ve done to address the gap (but not including any results!).

Methods

This section is more listy and matter-of-fact. Still, it can be helpful to separate it into sub-headings such as Data, Key outcomes and covariates, Model, Statistical approach, and Ethical considerations. When drafting, don’t get to caught up on the particulars; just write what you need to write. Later, you can download papers from your target journal and see what their conventions are.

Results

This secton is also matter-of-fact. Sticking to this matter-of-factness can be one of the most challenging things for budding scientific writers. It’s so tempting to present a result and then to say something about how meaningful and cool it is. Avoid this temptation! That’s what the Discussion is for. The Results is for numbers, confidence intervals, tables, figures, and not much else.

Discussion

This is where you get to have fun. Begin by re-iterating, in a sentence or two, what you’ve found, but do it in a more conversational tone. Then, start the zoom-out: tell the reader how they should interpret your results, why they matter, and what new avenues of research you’ve opened up. This can take anywhere from one to a handful of paragraphs - there’s no real limit here, other than the word limit that the journal imposes.

Then, you’ll need to devote a handful of paragraphs to your work’s limitations. Tell the reader both what biases you think have crept into your work and the way in which those biases might have affected your findings. It’s really important to walk the reader through this! You don’t want to be in the position of listing a bunch of problems with your work, and leaving the reader with the sense that you’re not a principled, rigorous scientist. Instead, raise the biases, tell the reader how they might affect your findings, mention if you’ve done anything to try to correct for them, and discuss ways that they might be addressed through future research. This section essentially lays out the gaps for your future research!

It’s helpful to conclude the Discussion with a few concluding sentences. Never, ever end a paper with a sentence like “More research is needed to…”. That’s for the Limitations. The conclusion should re-iterate the importance of the problem, shed some new light on the remaining challenges, and entice the reader to care deeply about the problem you’ve just told them about.

Style

Scientific writing is no longer supposed to be dry and impersonal. Dry scientific writing was the result of the misguided belief that the scientist should be totally detached from the science, and thus should be absent from any descriptions of the science. This led to awful paragraphs full of passive voice, with inanimate objects marching through all sorts of transitions as if by magic. The philosophy of science has matured, and we now understand that no science is truly objective. Therefore, it is ok, and encouraged, to use “we”.

Using “we” often helps you to speak in active voice (passive: “the simulations were run on…”; active: “We ran the simulations on…”). Active voice is almost always easier to understand and more pleasurable to read.

Use simple words. You didn’t “endeavor” - you “tried”. This applies to both non-scientific and to scientific words. Jargon is your enemy. When you can’t avoid using big words, help the reader with a description in parentheses: we collected samples using combined anterior nares and oropharyngeal (nose and throat) specimens.

Use short sentences. Sentences should contain one idea each. Use find-and-replace to find semicolons and hyphens once you’ve finished writing your manuscript. Take out any that could be replaced with a period.

When possible, write in the past tense. The manuscript describes something that you or others did in the past. This is true for the introduction, methods, and results. Sometimes the present or future tenses can justifiably sneak into the Discussion, but if you use them, make sure you have a reason to.

One of the most challenging parts of scientific writing is giving the prose a direction, rather than making it a list of true statements. One way to achieve this is to pay close attention to the beginnings and endings of your sentences. The first and last words of a sentence are the most important. Make sure they count. Try to conclude sentences with a word that foreshadows what the next sentence will be about. Note that this rule could cause you to introduce some passive voice into your manuscript. That’s ok! Most of the time, active voice will be compatible with flow, but when it’s not, prioritize flow.

Papers should be interpretable by reading just the first sentence of each paragraph. Make sure that all of your paragraphs are structured such that the topic of the paragraph is right at the beginning. If the topic shifts midway through, make a new paragraph. Short paragraphs are fine.

There are loads of style books out there to help with composing manuscripts. I especially like Strunk/White’s “The Elements of Style”. These are often worth their weight in gold!

Tools

There are many different tools to help you get from an idea to a finished manuscript. Here are a few that I’ve used:

Planning

- Scapple: This is an intuitive, flexible mind-mapping software that can be helpful for figuring out how ideas relate and how you’d like to structure your arguments.

- Scrivener: Made by the same team that created Scapple, Scrivener is a widely used platform for converting disconnected ideas into a full first draft. It allows you to put your ideas onto electronic post-it notes that you can easily re-order as your manuscript takes shape.

Writing

- Microsoft Word: It’s klunky, but it’s gotten better, and everyone uses it. It has a nice system for commenting, so depending on your collaborators, it may be the best tool for the job.

- Google Docs: Basically the online version of Microsoft Word. This is especially useful if you’re going to be collaborating with another author in real-time. Adding references can be a pain, but PaperPile helps.

- LaTeX: This is popular in mathy circles. It allows you to generate beautiful drafts with minimal effort, though the learning curve can be steep, since it’s more like coding than like what-you-see-is-what-you-get writing (a la Microsoft Word or Google Docs).

- Overleaf: This is an online LaTeX emulator that has good support for commenting on and sharing drafts. It’s the Google Docs of LaTeX.

Publication venues

There are a lot of different journals out there, each with different formatting requirements, different interests, and different protocols for getting from submission to publication. Often, it’s best to match a manuscript to a journal based on (1) do your figure and word counts fit easily into one of the journal’s submission formats? and (2) has the journal published related ideas?

Medical journals (e.g., the New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA and sub-journals, Lancet and sub-journals, PLOS Medicine, Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases) are open to public-health oriented work, but have an ultimate focus on clinical practice, so if you’re aiming for one of these, make sure that there’s clear clinical relevance.

Epidemiology-specific journals (e.g., American Journal of Epidemiology, International Journal of Epidemiology, Epidemics) are good homes for population-level analyses that don’t have a direct clinical impact.

For biological findings, you may want to target your work towards bio-focused journals, like PLOS Biology, PLOS Computational Biology, or eLife. These latter journals have much more free-form submission instructions (you can basically include as much text and as many figures as you want), so they’re also good homes for especially long pieces!

The publication process

In general, when you’ve finished drafting a manuscript and chosen a journal, you’ll upload it to the journal’s online submission portal. These, as a rule, are klunky and frustrating to use. I’m not sure why, but there are very few exceptions.

Sometime before formatting your final document for submission, it’s helpful to click through the submission portal to make sure you’ve accounted for everything you’ll be asked for. Often, the portal will introduce surprise new requirements that aren’t listed anywhere on the journal’s website. You’ll save yourself time and frustration by looking out for these things early.

In addition to the mansucript, journals often require a cover letter, which I’ll write for trainees who are just getting started, and which I’ll co-write with trainees later on in their training. These are one-page summaries to explain to the editors what you’ve done and why it matters, using more straightforward and high-flying prose than you can use in the actual manuscript.

You’ll also often have to look up a bunch of mundane information about your coauthors (emails, institutions) and you’ll usually have to propose between three and five suggested reviewers. It’s usually good to scan through the works you’ve cited and select reviewers from the author lists in your References.

After you submit the article, you’ll usually not hear anything for about two weeks. If the article has been desk rejected (i.e., the editors have decided they don’t want the piece, before sending it out for review), you’ll get an email notifying you of that fact. Then it’s time to aim for a new home. Otherwise, the article is sent for review, where the editor finds 2-3 (sometims up to 4 or 5) individuals in your field, loosely defined, to read and comment upon the accuracy and value of your work. This can take a long time, sometimes months. When you get the reviews back, the editor then makes a decision: either they will reject your paper (and send you the reviews so that you can incorporate some of them when you submit to a new journal), or will ask for a revise and resubmit. The revise and resubmit can entail anything from correcting typos to running many new experiments. It’s then up to you, the author, to decide if it’s worth your time to make those edits, or instead to try your luck at a different journal.

If you do decide to revise and resubmit, the journal usually gives you a few weeks to do so. You then will upload and submit the revised version (usually a clean copy and a tracked-changes copy). You will also include a copy of the reviewer’s comments with a point-by-point response detailing what you’ve done to address each request, or (more rarely) why you’ve decided not to.

Your re-submission may go back out for review, or the Editor may look through your revisions and deem them sufficient for publication. If it goes for review, then it’s a rinse-and-repeat of the previous steps. If it’s accepted, then congratulations! Your work has found a home! You’re not done yet, though, because the journal will eventually send you a list of edits to make sure that the writing is in accordance with the journal’s style rules. Once you’ve finally made it through that process, take a deep breath: you’re done!

It’s important to note that the review process can be unbelievably stochastic. Works of high value often get rejected, and works of questionable value sometimes get accepted at surprising places. One of the tasks of a scientist-in-training is to slowly cultivate a sense of detachment from the outcomes of any particular submission. This is difficult - I still hate it when I get things rejected - but it’s a fact of scientific life (for now, until we find a way to overhaul the publishing system), so it’s best if we find a way to make some kind of peace with it amidst all the frustrations. I’m here to help with that, too.

For more information, you can also check out Dan Larremore’s slides on peer review.